Translate this page into:

A rare presentation of cubital tunnel syndrome by accessory anconeus muscle

*Corresponding author: Vinoth Thangam, Department of Radiodiagnosis, A.C.S. Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. vinoththangam14@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Gadiraju B, Thangam V, Radhan P, Kumar V. A rare presentation of cubital tunnel syndrome by accessory anconeus muscle. Indian J Musculoskelet Radiol. 2024;6:45-8. doi: 10.25259/IJMSR_18_2023

Abstract

Cubital tunnel syndrome (Cu TS) is the second most frequent upper extremity compressive neuropathy after carpal tunnel syndrome. Cu TS is idiopathic; however, it has been linked to ulnar nerve vulnerability and anconeus epitrochlearis (AE) muscle hypertrophy. Although there are few studies in the literature that reveal AE muscle as one of the causes of Cu TS, its prevalence is low. The goal of this case report is to raise awareness regarding the existence of AE muscle as a potential cause of Cu TS, as well as the imaging findings of Cu TS in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A 17-year-old male patient complained of intermittent pain in the medial aspect of the left elbow and paresthesia in the left hand. Examination revealed hyperextension of meta carpalphalangeal joints and flexion of proximal interphalangeal joints of the 4th and 5th digits, besides the sensory deficit along the ulnar border of the 5th digit. A nerve conduction study revealed non-stimulable sensory and motor components of the right ulnar nerve. MRI with T1-weighted fast spin echo, Fat sat proton density-weighted, and gradient echo T2*-weighted sequence showed AE - on the posteromedial aspect of the elbow. The ulnar nerve within the cubital tunnel appeared thickened and edematous with bright perineural fat signals with maintained fascicular architecture, secondary to compression by the anconeus muscle. This paper reviews imaging findings of ulnar neuropathy secondary to accessory anconeus muscle and explains the importance of MRI imaging for accurate diagnosis. Knowing MRI imaging is vital in the modern imaging era for accurate diagnosis.

Keywords

Anconeus epitrochlearis

Cubital tunnel

Ulnar nerve

Magnetic resonance imaging

Nerve entrapments

INTRODUCTION

Anconeus epitrochlearis (AE) is an accessory muscle of the upper limb in the medial aspect of the elbow. It is a congenital accessory muscle present in 4–34% of the general population.[1] Originating in the medial epicondyle of the humerus, it inserts onto the olecranon process of the ulna, covering the posterior aspect of the cubital tunnel.[2] By substituting the more accommodating AE muscle for the natural cubital tunnel ceiling (Osborne’s ligament), the chance of getting cubital tunnel syndrome (Cu TS) would be decreased. AE involvement in ulnar neuropathy would result from subsequent muscle hypertrophy, increasing the likelihood of occurrence in the dominant arm.[1]

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old male presented with complaints of paraesthesia of the fourth and fifth fingers of the right hand. He also had difficulties in doing his day-to-day activities, like holding a pencil.

The symptoms were insidious in onset and had progressed gradually. There was no history of trauma to the right elbow or recent infections.

On examination, there was point tenderness over the medial aspect of the right elbow. There was hyperextension at meta-carpal phalangeal joints and flexion at proximal interphalangeal joints of the 4th and 5th fingers, consistent with features of claw hand. Flattening of the hypothenar eminence of the right hand was noted, along with sensory deficit along the ulnar border of the little finger [Figure 1].

- A 17-year-old male presented with features of claw hand.

A nerve conduction study revealed that the sensory and motor components of the right ulnar nerve were not stimulable.

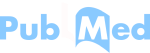

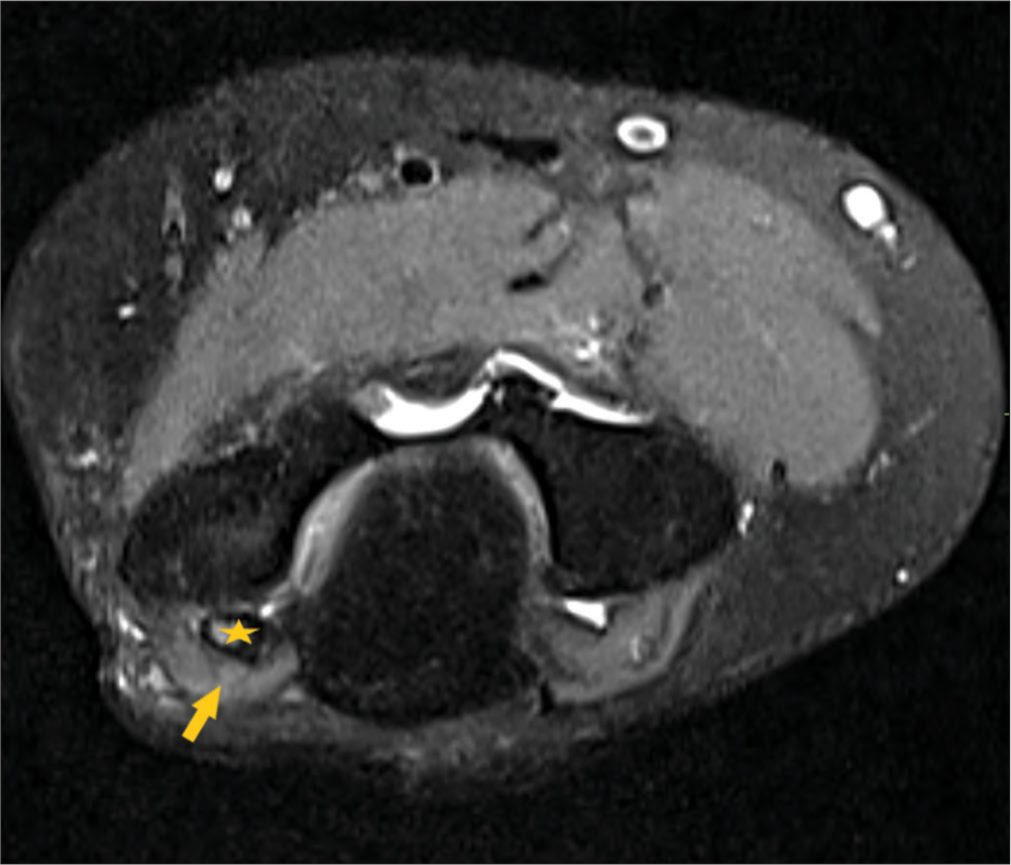

Further evaluation with a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the elbow and wrist was done, which showed an accessory AE muscle forming the roof of the cubital tunnel measuring 14 × 10 × 4 mm (cranio caudal × transverse × anteroposterior). It is observed that the cubital retinaculum and the AE muscle, which constitute the ceiling, are inseparable. Mild soft-tissue edema was seen in the subcutaneous plane over the cubital tunnel and olecranon. The edema extended proximally from the visualized distal arm and distally to the mid-forearm level centered at the cubital tunnel [Figures 2 and 3].

- Fat-suppressed proton-density-weighted turbo spin-echo axial section showing the anconeus epitrochlearis muscle (arrow) forming the roof of the cubital tunnel. Note the thickening of the ulnar nerve within the cubital tunnel (star).

- Fat-suppressed proton-density-weighted turbo spin-echo sagittal section showing ulnar nerve (arrow) with bright signal intensities. Note that the ulnar nerve is thickened and edematous within the cubital tunnel.

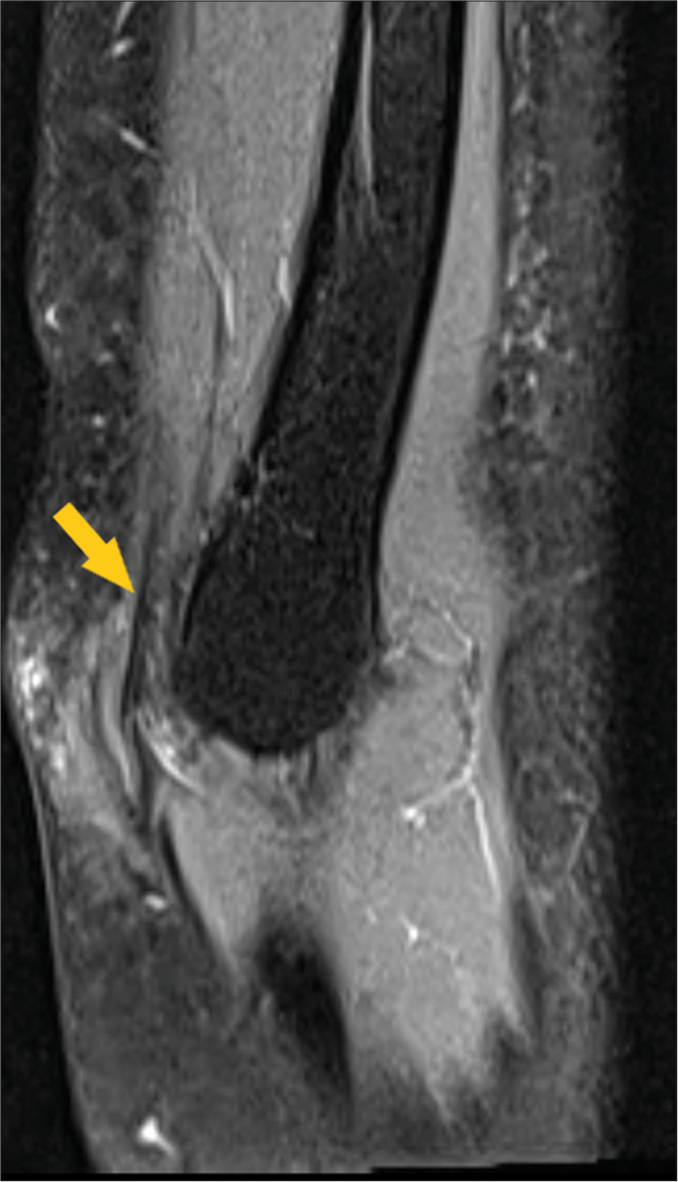

The ulnar nerve within the cubital tunnel was diffusely thickened and edematous, showing intrinsic bright signals (on T1-weighted fast spin echo and gradient echo T2* weighted sequences) with maintained fascicular architecture [Figure 4].

- Short-tau-inversion-recovery sagittal section showing ulnar nerve (star) with bright signal intensities. The anconeus epitrochlearis muscle (arrow) is seen forming the roof of the cubital tunnel.

DISCUSSION

AE is a triangular muscle originating in the medial epicondyle of the humerus. It inserts laterally on Osborn’s ligament and proximal posterior surface of the ulna. [3] The position of AE is best visualized just distal to the medial epicondyle, especially on axial sections where the relationship between the ulnar nerve and adjacent soft tissues could be demonstrated.[4] Usually, this muscle is probably atavistic and is replaced by a band passing in the same direction as the muscle known as the epitrochlearis ligament.[5] This AE muscle replaces the normal roof of the cubital tunnel (Osborn’s ligament) with a forgiving muscular structure, thereby reinforcing the roof of the tunnel. In this way, the AE muscle acts as a preventive mechanism against ulnar nerve compression within the cubital tunnel. When the elbow is moved into flexion from extension, there is increased neural pressure as the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the cubital tunnel is decreased.[6] The prevalence of hypertrophied AE muscle is more common in the dominant hand.[7]

However, the hypertrophied AE muscle in the cubital tunnel is found to be more common in younger age groups.[8] These patients would usually present with a shorter duration of symptoms with rapid aggravation. MRI is also found to be an adjunct to the clinical examination and nerve conduction studies in diagnosing this condition. Clinical presentation typically includes hypoesthesia or sensory deficit in the fourth and fifth fingers, atrophy of the intrinsics fourth intermetacarpal space, difficulty with fifth finger abduction, and loss of strength.

Ultrasonography could be an aiding tool in diagnosing Cu TS. The sonographic CSA of the nerve will be an important deterministic factor in diagnosing neuritis. The CSA of the ulnar nerve at the level of the medial epicondyle is different in the patients as compared to normal individuals. CSA of >10 mm2 is considered to be a cutoff in diagnosing ulnar neuritis sonologically.[9]

MRI is found to be the imaging modality of choice because of its ability to demonstrate the anatomy with great detail. Moreover, the cause of entrapment could also be established with the help of MRI. Moreover, notable abnormalities were found with MRI in 90-97% of cases compared to 63-77% with neurography, which means that the sensitivity of the MRI is significantly higher. The findings in MRI include focal hyperintensity of the ulnar nerve in T2 weighted imaging. There could also be the thickening of the ulnar nerve in the involved segment.[10] Associated abnormalities like tendinopathies (biceps, common extensor tendons) are commonly found in patients with AE muscle. Hyperintensity of the nerve in T2-weighted images may not pertain to the specific feature since it’s also present in 60% of the asymptomatic elbows. Images must be taken with the same degree of flexion throughout the elbow and forearm level, as elbow flexion decreases the CSA of the nerve.

CONCLUSION

The present case suggests that certain anatomic variables may cause compression along the ulnar nerve, resulting in Cu TS. AE is one such etiology causing ulnar nerve compression. MRI has been a reliable modality in diagnosing this present case because of its various sequences, which explain the soft tissue anatomy in detail. Definitive management will be the complete decompression with open surgery and excision of the accessory muscle.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge our faculty members of Department of radiodiagnosis for helping us draft this article and for their constant support throughout.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient consent not required as patient identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Variant of the anconeus epitrochlearis muscle: A case report. Cureus. 2018;10:e3201.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anconeus epitrochlearis muscle associated with cubital tunnel syndrome: A case series. Hand (N Y). 2019;14:477-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accessory muscles: Anatomy, symptoms, and radiologic evaluation. Radiographics. 2008;28:481-99.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MR imaging of edematous anconeus epitrochlearis: Another cause of medial elbow pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:103-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The cubital tunnel and ulnar neuropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:613-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changes in interstitial pressure and cross-sectional area of the cubital tunnel and of the ulnar nerve with flexion of the elbow. An experimental study in human cadavera. Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:492-501.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The anconeus epitrochlearis muscle may protect against the development of cubital tunnel syndrome: A preliminary study. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:1533-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubital tunnel syndrome caused by anconeus epitrochlearis muscle. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2018;61:618-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubital tunnel syndrome: A review and management guidelines. Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2011;72:90-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulnar nerve cross-sectional area for the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome: A meta-analysis of ultrasonographic measurements. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:743-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]